BC Hydro’s Integrated Resource Plan does not take seriously enough the possibility of a large increase in demand for electricity, and treats the government’s CleanBC Plan as a “risk” rather than established policy. The BCUC’s review was not forceful enough in pointing this out.

Introduction

A recent report by Clean Energy Canada evaluated the Canadian provinces on “progress towards building a sustainable economy”, rating BC as a “B” overall. Despite getting an “A” in the clean buildings and clean transportation categories, the province only managed a “C” for clean energy. The main cause for this poor grade was energy system planning and slowness in procuring new energy resources.

The report claimed there was a “disconnect between its climate policy and its energy system planning” and that planning by BC Hydro, the province’s largest electricity utility, provided “insufficient detail on how we plan to meet the power demands of existing climate policies, let alone those of a net-zero 2050.”

How do these claims stack up?

BC Hydro’s Integrated Resource Plan

BC Hydro recently completed its Integrated Resource Plan, a 20-year view of the utility’s forecast need for electricity and how it will meet that need. The BC Utilities Commission (BCUC) has the jurisdiction to review the long-term resource plans of public utilities in BC.

There are three key questions that the Integrated Resource Plan should answer:

- How much electricity will be needed over the next 20 years?

- What is the best way to provide any additional electricity needed?

- What short-term actions are needed to ensure a safe and reliable supply?

How much electricity will be needed?

As Yogi Berra perceptively noted, it’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.

Rather than making one precise (and almost certainly incorrect) forecast of the future need for electricity, utilities prepare multiple forecasts for different scenarios, each with its own set of assumptions. That way, they can plan for different scenarios, and ensure that they are ready to provide safe and reliable service at a reasonable cost whether demand for electricity goes up or down or stays the same.

For scenario planning to be effective, it must cover a wide range of possible outcomes. It is important to plan for more extreme scenarios, even if they are not very likely to happen. If planners don’t show sufficient courage and imagination, and any of the more extreme scenarios actually come to pass, a utility may be unable to serve its customers, at least at any reasonable cost.

BC Hydro’s reference scenario

Central to the Integrated Resource Plan is the “reference” scenario, which BC Hydro argues creates the “expected or most likely” forecast; that is, its “best assessment of expected electricity demand”. Over the 20-year planning horizon, the reference forecast projects what BC Hydro refers to as “moderate growth” of about 1.4 percent per year.

Like all forecasts, it’s based on a series of assumptions. For example, the reference scenario uses an August 2022 economic forecast from the Conference Board of Canada showing long-term economic growth (2030 to 2045) “averaging around 1.7 per cent”.

But perhaps the most critical assumption in the reference scenario is that it only includes the effects of “legislative and policy measures related to electrification that were already in place or were close to being enacted at the time of forecast development [April 2023].”

And here’s the problem. All the “legislative and policy measures” that are not yet in place or close to being enacted, but which will be necessary to meet the government’s climate policy goals, including the goal of net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050, are not in the reference scenario or forecast. This is a serious disconnect between the Integrated Resource Plan and the BC government’s climate policy.

And the disconnect is not just about policy goals. The GHG emission reductions are set out in the BC Climate Change Accountability Act. But as I’ve pointed out before, the government has already repealed one legislated target (for 2020), and may be tempted to do so again.

Acceleration electrification scenario

BC Hydro did not completely ignore the government’s climate policy goals, however. One of the “key risks and uncertainties” to the reference forecast is the “possibility of a large and rapid increase in low carbon electrification through climate change mitigation policies.”

Presumably to account for this “risk”, BC Hydro added an “acceleration electrification” scenario in its Integrated Resource Plan. This scenario assumes, unlike the reference scenario, that “All provincial greenhouse gas emission reduction targets are met over the milestone years of 2025, 2030 and 2040” (the Integrated Resource Plan covers the years 2023 – 2043, so does not include the 2050 net zero goal).

BC Hydro based its acceleration electrification forecast on a model created by Navius Research Inc. The Navius model assumed that new legislation and policy would be put in place to meet the legislated GHG emission reduction targets, and that significant additional electricity demand would come from electrification of the natural gas sector and buildings.

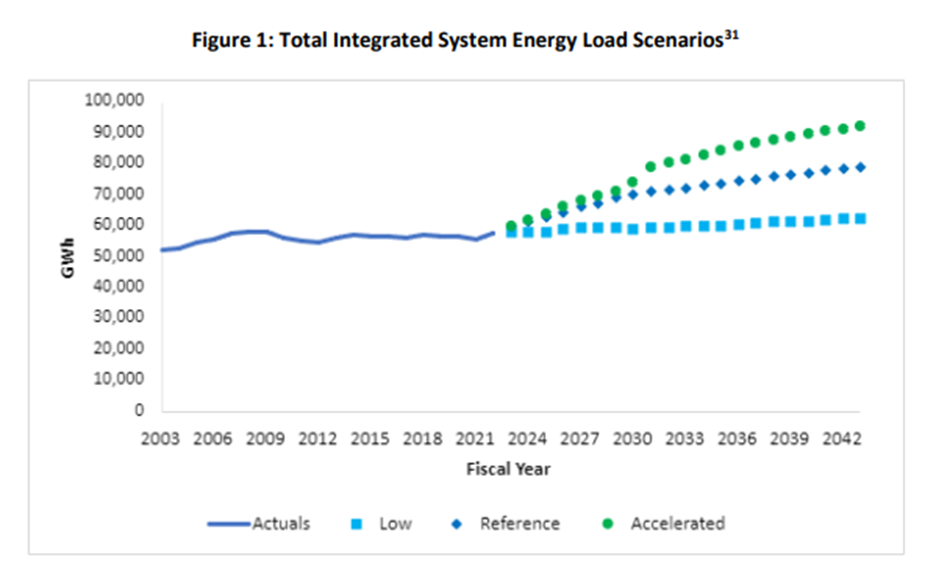

Unsurprisingly, the acceleration electrification scenario requires a lot more electricity, as the following graph, prepared by BCUC staff based on BC Hydro data, illustrates:

Surprisingly, BC Hydro does not consider accelerated electrification to be the “expected or most likely” forecast, but it has at least considered the effect of government actually doing what it says it will.

But the story is not over yet.

North Coast LNG and Mining Scenario

BC Hydro also analyzed the potential demand for electricity from liquified natural gas (LNG) and mining facilities that may “materialize” in the north coast region of BC over and above what is contained in the reference scenario. This “North Coast” scenario assumes that “several” of these LNG and mining facilities go ahead with in the next decade, powered by electricity rather than fossil fuels.

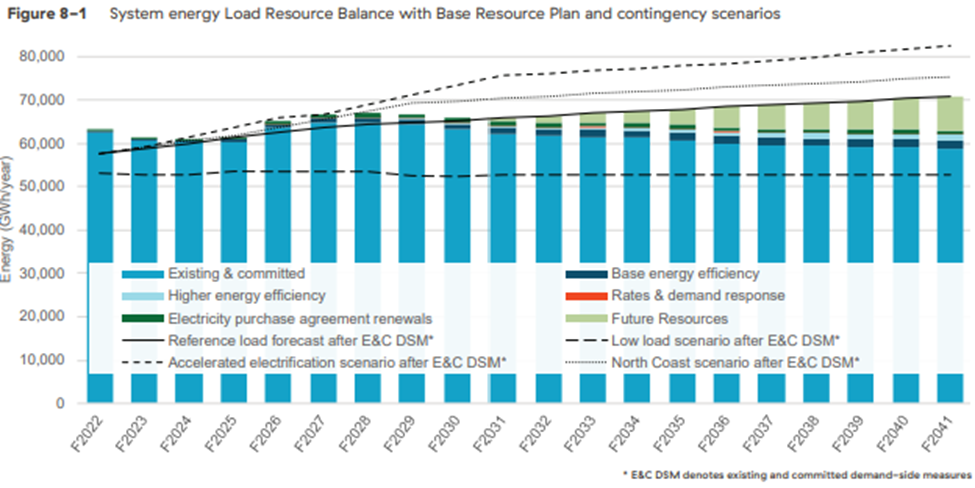

Unfortunately, as you can see from BC Hydro’s chart below, it only considered accelerated electrification or the North Coast scenario:

The Integrated Resource Plan did not consider a scenario where both the BC government achieves its GHG emission reduction targets, and we have new mining and LNG electrification on the north coast.

This is a serious omission. It means the Integrated Resource Plan has not considered how, or even if, BC Hydro could serve both sources of new electricity demand. Whether both events are likely to happen together is not the point – they could, and we should understand the implications if they do.

This is yet another disconnect between climate policy and energy planning. The BC government recently noted the opportunity to export “low or zero emitting Canadian LNG,” and is anticipating over $1.4 billion in natural gas royalties by the 2026/27 budget year – quite an increase on the $161 million received in 2017/18. It is far from clear that BC Hydro’s Integrated Resource Plan will be able to deliver the electricity required for the “low or zero emitting” LNG that BC is hoping to export.

The BCUC’s review

After a lengthy review, the BCUC accepted BC Hydro’s plan as being “in the public interest”, the test set out in section 44.1 of the Utilities Commission Act. In my opinion, the BCUC was not critical enough of the above-noted deficiencies in BC Hydro’s planning.

The BCUC found BC Hydro’s load forecasts to be “reasonable” because the methodology used to create them was “consistent with its accepted past approach” and because they “consider a range of future uncertainties.” While both points are true, this is faint praise indeed.

As the BCUC itself noted, BC is “in the midst of an energy transition.” This seems like a reason not to use the same approach to creating forecasts that was used in the past. And, while there was “a range of future uncertainties” this range wasn’t nearly comprehensive enough.

The BCUC did note that “there are possible scenarios where the demand could exceed [the acceleration electrification scenario]”, so why not demand that BC Hydro expand its analysis to consider such “possible scenarios”? Looking at possible scenarios is the point of scenario planning!

The BCUC didn’t even direct BC Hydro to evaluate these scenarios in the next planning cycle, saying rather weakly that it expected that “BC Hydro’s internal load forecasting and scenario development practices will examine the appropriate range of scenarios for its long-term planning purposes.”

Conclusion

This is the first time in 15 years that the BCUC has reviewed a long-term plan from BC Hydro. After the commission rejected BC Hydro’s 2008 Long Term Acquisition Plan, the government took over planning the state-owned business itself, and only gave the review role back to the BCUC in 2021.

It is understandable that the BCUC might be cautious about rejecting the plan, even in part, which the Utilities Commission Act permits it to do. No doubt it doesn’t want the government to take away its supervisory role over BC Hydro’s planning again.

And I’m sure the BCUC was also cautious, with an election coming in October, that it might be seen to challenge the government’s assertion that it can achieve the province’s GHG emission reduction targets while simultaneously pursuing clean LNG exports and mining projects.

The problem, though, is that the BCUC is the only independent body with the power to critically review BC Hydro’s plans, which are essential to the energy future of the province. By failing to plan now for the amount of electricity we need, we may end up paying a much bigger price for it later, or even having to resort to rationing (actually, we already are rationing electricity in BC).

But perhaps my sound and fury are misdirected. The premier’s public expectation of the Minister of Energy is that she will develop a “climate-aligned energy framework.” There are rumours that this innocuous-sounding phrase refers to a fully-fledged provincial energy plan, of which BC Hydro will surely be a key component. If so, will it be developed behind closed doors and without the scrutiny that the BCUC could, at least in theory, provide?

Maybe the BC Hydro-BCUC relationship isn’t the only thing we should be worried about.

Future articles

I have focused here on how the BC Hydro Integrated Resource Plan illustrates a disconnect between government climate policy and energy planning, but there are plenty more issues with this plan. In future articles I intend to address:

- Is BC Hydro making the right choices for new electricity supply?

- Is BC Hydro taking the right short-term actions to meet future electricity demand?

- Will we have enough electricity to power the CleanBC plan, and achieve net zero GHG emissions by 2050?

Watch this space.