One pipeline proposal accepted, another rejected. What will the BCUC do next?

Introduction

Last month, the BC Utilities Commission (BCUC) approved an application from Pacific Northern Gas (PNG) to build a 650-metre pipeline extension near Prince Rupert, BC (the Ridley Island Decision). The extension will meet the additional demand for natural gas at the new Ridley Island Energy Export Facility. All perfectly routine, nothing to see here.

But less than two years ago, the BCUC rejected an application from FortisBC Energy Inc. (FEI) to upgrade a gas pipeline serving customers in the Okanagan region of BC (the Okanagan Decision). The expansion would have met the additional demand for natural gas from new customers in and around Kelowna.

The BCUC agreed that PNG’s and FEI’s proposed investments were both needed, but came to different conclusions about each project.

What the dickens is going on?

Background

By law, utilities require approval from the BCUC before they build or expand infrastructure such as gas pipelines, which will only be granted if the BCUC decides approval is in the public interest. First and foremost, utilities must demonstrate the need for their projects.

It’s not quite that simple, though. Utilities are compensated for the amount they invest in equipment; in fact, it’s generally the only way they can profit from regulated services. The BCUC must make sure that a proposed project really is necessary, and, for example, that there are no cheaper ways to achieve the same ends.

But still, utilities are legally obligated to provide safe and reliable service and to connect new customers who want service, so if a utility can convince the BCUC that an investment is needed to keep up with demand and service levels, it stands a good chance it will be approved.

The BCUC has wide latitude to use its own judgement when deciding what other “public interest” factors should be considered, including risk. In both these decisions, risk was a key factor.

Ridley Island

The need for the Ridley Island project was relatively easy for PNG to establish. The new pipeline will deliver gas to an export terminal for liquified petroleum gas and bulk liquids, currently under construction. PNG’s customer, Alta Gas, has signed a minimum 10-year contract to buy gas from PNG on a guaranteed “take or pay” basis.

The gas will be used to generate electricity at the terminal as there is “insufficient electrical infrastructure to provide reliable grid electricity” in the area, and the 10-year contract suggests that Alta Gas doesn’t expect BC Hydro to be delivering reliable power there any time soon.

But there is some risk that the pipeline will not be required for its entire useful life. If BC Hydro were to upgrade its facilities in the area, the export terminal might choose to replace gas generation with clean grid electricity. If that were the case, PNG’s ratepayers might have to pay for the now-redundant pipeline extension.

However, this risk has been managed. If Alta Gas decides to terminate its contract early, it will pay a disconnection fee to compensate PNG for the uncollected costs of the new pipeline, and PNG’s other ratepayers will not be left on the hook. This was the biggest single element of the BCUC’s reasoning for approving PNG’s proposal.

Okanagan

The Okanagan pipeline expansion was proposed to meet what the BCUC acknowledged was an “imminent capacity shortfall” in FEI’s gas system. Demand for gas in the Okanagan continues to grow, both from increased population and industrial demand, such as winery operations. FEI is obligated to serve these new customers.

By winter 2026/27, FEI predicts it may no longer be able to provide safe and reliable service in the area. A prolonged cold spell could cause communities in the Okanagan such as West Kelowna to be disconnected due to low pipeline pressure.

But demand in the Okanagan is not guaranteed to keep growing as it has in the past. The BCUC pointed to government policies and regulations, such as the BC Energy Step Code and Zero Carbon Step Code, that may in future prevent new buildings from using gas for space and water heating. Current growth trends may slow or even reverse.

If the government is successful in lowering GHG emissions, FEI’s ratepayers would still bear the cost of the pipeline extension. The BCUC wasn’t willing to commit FEI’s ratepayers to that risk, and ordered FEI to look into short-term alternatives instead.

Risky business

Considering risk to ratepayers is fine, as long as the risks are properly identified. The Ridley Island decision seems reasonable enough, but the attempt to protect FEI’s consumers from the cost of a possibly unnecessary Okanagan pipeline expansion is already looking suspect.

The BCUC recently approved a short-term fix for FEI to deliver liquified natural gas to Kelowna by truck during the summer, store it there in tanks, and inject it into the pipeline in the winter if it’s needed. This will only be sufficient until 2029, but will still cost $50 million (the 65-year solution was $327 million). We have no idea how many other short-term measures will need to be added before peak demand starts to drop, if it ever does, and how much they will cost.

The BCUC considered the risks of approving the Okanagan project, then decided against it. However, it appears the BCUC didn’t evaluate the risks of the decision it actually made – to reject the proposal.

And not just the financial risk. If FEI runs out of short-term options, we’re back to the problem that it was trying to solve in the first place – the risk that whole communities will lose their gas supply, possibly for weeks, and not be able to heat their homes or run their businesses. The BCUC’s faith in the government’s GHG emission reduction plan is touching, but it might be wise to consider the possibility that its faith is misplaced. The history of GHG emission reductions in BC is not encouraging.

If the BCUC is going to use risk as a criterion when evaluating utility investments, it should be sure to do a comprehensive risk assessment of rejecting applications as well as approving them.

Next up!

Risk will also be a big factor in another decision that the BCUC will be making shortly. FEI has applied to replace its aging liquified natural gas storage facility at Tilbury in Delta, BC, currently the “last resort” to meet winter peak demand in the Lower Mainland.

The BCUC faces a choice of risks. Approving the proposed $1.1 billion project carries a similar risk as the Okanagan decision – if gas demand declines in future decades, the usefulness of the assets is reduced, but ratepayers must still pay for them – except that the cost for Tilbury is much higher.

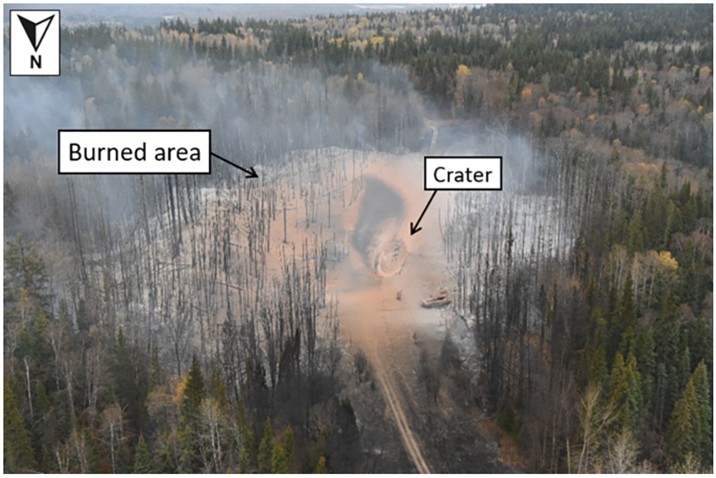

In the case of Tilbury, though, there’s also a significant non-financial risk to rejecting the project. The facility provides a short-term supply of gas if the main pipeline serving Vancouver is interrupted, a so-called “no-flow event.” This is not just a theoretical risk, it actually happened in October 2018. The location of the event that caused this particular lack of “flow” is shown in the photo below:

In October 2018 we were lucky. The weather was mild, so gas demand was lower than it would be in the winter. Also, the explosion happened a considerable distance from Vancouver, which meant there was some “line pack” (compressed gas) in the pipeline downstream of the break that could still be delivered. Despite this, Vancouver came close to running out of gas, and FEI claims there have been two “near misses” since 2018.

Conclusion

The BCUC is correct to consider risk when evaluating proposed investments by utilities, but the analysis must be sufficiently comprehensive. It’s not enough to look only at the risk of the actions that are rejected, and ignore the risk of what is approved.

The Tilbury decision will be particularly challenging. It’s unlikely the BCUC will reject the proposal to replace the storage tank outright; it performs an important peak-supply function today, and the gas network will still be around, in some form, for decades to come.

But FEI has proposed expanding the existing storage facility, not just replacing it. The extra capacity would provide additional days of backup in the event of a pipeline outage, and FEI claims this is good value for money (the smallest replacement option represents 73 percent of the capital cost of the largest alternative).

The BCUC must decide whether it’s worth the additional cost to reduce the likelihood of 600,000 customers losing gas for many weeks, with the attendant human and economic cost.

Hard times indeed!

One final thought

It would be helpful if there was more clarity about the future of BC’s gas system.

There’s a lot of talk about electrification, but so far most of this has focused on the electricity sector and BC Hydro’s struggles to add sufficient generation. Almost never discussed is the other side of the same coin – what happens to the gas system as we electrify? Should it remain its current size? Be repurposed? Shut down? And if so, how?

A clear plan for the gas system in BC might help the BCUC make more informed, and less risky, decisions about future gas utilities’ investments.