A reader asked recently about the future of rooftop solar and net metering in BC, and how these could help meet future electricity demand. My response was that we should wait for the outcome of BC Hydro’s Integrated Resource Plan proceeding.

The BCUC’s decision was issued on March 6, 2024. Sadly, there’s not much to report; the decision doesn’t mention net metering. But there were some clues. Here are some thoughts on where we might be heading.

What is net metering?

Net metering is a voluntary arrangement that allows utility customers who generate their own electricity, typically from rooftop solar panels, to “bank” any excess electricity they can’t use, and to retrieve it later when it’s needed. Both BC Hydro and FortisBC have net metering programs for their residential and commercial customers in the province, but this article will focus on the larger BC Hydro program.

In 2019, 1,817 (98 percent) of BC Hydro’s net metering customers used solar panels. Most of the remainder used some combination of solar, hydro-electric and wind power.

Customer self-generation does not require a net metering program; customers could still install rooftop solar panels for their own use without having the banking arrangement for surplus energy. But a net metering program provides such a significant incentive that they are viewed as being almost inseparable.

Benefits

Net metering gives self-generating customers an incentive to invest in their own generating facilities.

Estimates of the payback period for installing residential solar panels vary widely, between 5 and 15 years. This depends on many factors, including the price of the installation and the cost of the energy displaced, but the more energy from the solar panels that can be used, the shorter the payback period will be.

Without a net metering program, any surplus energy produced would be wasted. The net metering program allows self-generating customers to use surplus energy when they need it, avoiding further electricity charges to their utility, and shortening the payback period for their investment.

Utilities can also gain, by avoiding having to generate the energy produced from their self-generating customers.

What’s the plan?

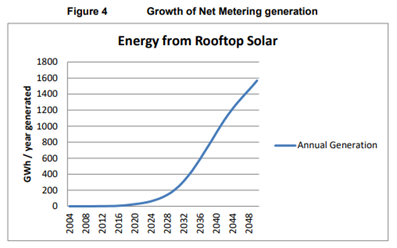

In its 2021 Integrated Resource Plan, BC Hydro forecast it would avoid having to generate 62 GWh in 2024 as a result of self-generation by net metering customers, rising to almost 1,600 GWh by 2048, that’s a factor of 25:

While even 1,600 GWh is relatively small compared to BC Hydro’s overall generation (46,898 GWh in fiscal year 2024), it is quite significant considering the 5,100 GWh expected from the new Site C dam, which should be in service by fall 2025.

BC Hydro expects the increase in its net metering program (to 115,000 participants by 2041) will be driven primarily by a decrease in the capital costs of new solar systems and the improved payback period. In other words, the increase will occur naturally, as long as the cost of new solar systems does, in fact, continue to decline.

However, BC Hydro does not propose to provide incentives for customer self-generated solar energy. In its evidence, BC Hydro stated that there are “other more cost-effective means to meet the long-term energy needs of our customers” such as onshore wind power.

Self-generation potential

Rooftop solar generation is unlikely to be a major source of generation in BC, as it is in some other jurisdictions. In sunny California, for instance, the Public Advocates Office estimates that over 1.5 million households served by the state’s three largest electric utilities have rooftop solar. In more northerly BC, we simply get less sunshine.

But BC Hydro is now short of electricity again, the same situation that led to the creation of its net metering program in 2004. Furthermore, the BC government has set aggressive GHG emission reduction targets, which will require considerably more electricity as we transition to electric vehicles and other clean energy solutions.

The BCUC noted in 2020 that net metering had, in the past, been viewed by BC Hydro as an additional source of energy to help meet electricity generation requirements and that it “may well be viewed in this context beyond 2030.” Prophetic, one could argue.

How could changes to the net metering programs encourage more customers to generate their own electricity?

Here comes the sun

There are some barriers to the expansion of the net metering programs. One is simply a lack of awareness – more electricity customers need to know the benefits. This is a relatively low-cost problem to solve, if someone had the right incentive to do it. If the utilities are reluctant, then government or solar panel installers might want to step up.

Another barrier is the enrolment criteria for the net metering programs. FortisBC currently limits participants to facilities that are under 50 kW and do not exceed the customer’s annual demand. As the BCUC has noted, capacity limits can be a barrier to participation if customers are forced to install a smaller and less economically efficient generator than they otherwise would have done.

FortisBC could increase the maximum generator size to 100 kW, the same as BC Hydro’s limit. There may be safety and operational considerations, but it’s not clear why these would be different between the two utilities. Also, FortisBC could remove its rule that limits customers’ size of generating facility to their annual demand. If customers are willing to generate the additional electricity, why not take advantage?

But is 100 kW even the appropriate limit? Perhaps the limit should be higher, allowing commercial customers to connect larger facilities, solar or otherwise. This would no doubt require some investigation, but the BCUC could direct this to happen.

A proven way to grow self-generation is for the government to subsidize it, as California has done, but this is not necessarily cost-effective. The BC government will have to fund the expansion of BC Hydro’s own generation, being the utility’s sole shareholder, and has already announced investment of $36 billion over the next ten years (see note 3). This may be a better use of taxpayers’ money than subsidizing rooftop solar installations.

There are more creative ways to encourage participation. Virtual net metering, for example, allows larger customers such as municipalities with multiple meters to aggregate their demand, and offset the larger amount against their own generation. The BCUC requested in 2020 that BC Hydro consider virtual net metering, and took the view that the utility would have plenty of time to do so by April 2024.

There are likely other creative ways to expand these programs. If the utilities are not keen to explore them, the BCUC could take the lead.

California Dreamin’

Before the use of rooftop solar and other customer self-generation expands significantly, we need to address the question of cross-subsidies. This has led to controversy in California, and there are lessons we should learn from that experience.

According to an analysis by Severin Borenstein of the Energy Institute at Haas, customers of California’s three largest electric utilities got less than 2 percent of their electricity from rooftop solar panels in 2014; today this has risen to about 20 percent. As a result, he calculates that non-solar customers could each be paying US$300 per year to subsidize customers with solar panels and net metering.

How are self-generating residential customers subsidized by other customers?

Utilities such as BC Hydro have a high proportion of fixed costs, but most of their revenues come from a variable (per kWh) charge. As customers use less of BC Hydro’s energy because they have solar panels, they contribute less to BC Hydro’s fixed costs, causing BC Hydro to raise the per kWh charge for everyone to recover its total costs.

At the extreme, a BC Hydro residential customer using solar panels and the net metering program to meet their entire annual needs would pay no per kWh charge at all. They would just pay the basic charge of around $82 per year, compared to the average annual household bill of $1,237 (see note 1). But BC Hydro still needs to have all the assets in place to provide them with electricity when the sun isn’t shining, just as it does for a non-self-generating customer.

This problem can be addressed with a different rate design, where self-generating / net metering customers pay their fair share of BC Hydro’s fixed costs in a different way, something that’s now being explored in California.

Residential rate design options

One solution would be to increase the basic charge paid by all residential customers regardless of the volume they consume, and reduce the variable charge by a corresponding amount. Today, the basic charge is only around 6.7 percent of the average BC Hydro’s customer’s bill, despite the vast majority of BC Hydro’s costs being fixed (see note 2). Increasing the basic charge would ensure BC Hydro received more revenue even as customers generated more of their own electricity, but would have other, possibly undesirable consequences.

Another option would be a demand charge, already a feature of rates for non-residential customers such as commercial and industrial companies. Self-generating residential customers could pay a fixed demand charge based on the maximum amount of electricity they use, and a correspondingly lower variable charge than non-self-generating customers.

BC Hydro stated in October 2022 that it expects to file an application for changes to its net metering program “in the fall of 2023”, in which it would address issues such as virtual net metering. Sadly, this did not happen. The utility then said, in May 2023, that it was “currently working” on this application, and would submit it “no later than June 2024”.

By a happy coincidence, June 2024 is also the date the BCUC directed BC Hydro to file a residential rate design application. Of course, BC Hydro could request that the BCUC reconsider that decision, something it has done quite frequently of late. But as it stands, the date is still on the BCUC’s calendar of anticipated filings (although oddly the anticipated net metering application is not).

Let’s hope that BC Hydro files a net metering application in June 2024. If not, the BCUC may have to take a tougher line if it wants to move net metering forward.

A new dawn?

Rooftop solar generation and net metering don’t appear to have a very bright future in BC. Our utilities don’t seem enthusiastic, appearing to view them as something between a distraction and a threat.

But we are going to need considerably more electricity to transition the economy to electric vehicles, home heat pumps and the like. And BC Hydro and FortisBC will face increasing demand during peak hours, which will require considerable investment in both generation and transmission facilities.

If there is a potential game changer, it might be battery storage.

Battery costs are estimated to have fallen 97 percent between 1991 and 2018, and are forecast to decrease further between now and 2050; perhaps by another 50 percent. New technologies such as solid-state and sodium-ion batteries promise even better performance and / or lower cost.

Combining rooftop solar generation with battery storage allows customers to store some of their surplus electricity themselves, using it in peak hours when it’s most beneficial to them and their utility.

The BCUC recently approved an optional time-of-use rate for BC Hydro’s residential customers, giving participants an incentive to avoid using electricity between 4 and 9 pm, BC Hydro’s peak demand period. This rate is expected to be available starting in June 2024.

For a self-generating customer participating in BC Hydro’s time-of-use program, the savings on energy use between 4 and 9 pm will be higher if they use stored energy from their own battery, rather than retrieving the energy from their “bank account” at BC Hydro.

It remains to be seen whether the 5 cent / kWh incentive offered by BC Hydro is sufficient to shift as much demand from BC Hydro’s peak demand period as it hopes. Or, indeed, whether it is sufficient to compensate for the cost of adding a battery to a solar panel installation.

But at least it might stimulate some more interest in net metering.

Note 1

Annual average BC Hydro bill calculation:

Average use per year: 10,000 kWh (from BC Hydro)

Average use per billing period: 1,667 kWh (10,000 / 6 periods per year)

Basic charge per billing period: $13.52 (22.53 cents * 60)

Step 1 charge per billing period: $148.10 (1,350 kWh * 10.97 cents / kWh)

Step 2 charge per billing period: $44.59 (317 kWh * 14.08 cents / kWh)

Total charge per billing period: $206.20 ($13.52 + 148.10 + 44.59)

Total charge per year: $1,237.20 ($206.20 * 6)

Note 2

Basic charge calculation:

Basic charge per year: $82.23 (22.53 cents * 365)

Total charge per year: $1,237.20 (from above)

Ratio: 6.7 percent

Note 3

For clarity, the $36 billion investment announced by the government will be made by BC Hydro, and will be recovered from ratepayers in rates over the life of the investments. The government as BC Hydro’s shareholder provides only a portion of the $36 billion the utility requires to make the investments.