A lot has changed since the BC Utilities Commission (BCUC) reviewed the Site C project in 2017. How does the BCUC’s analysis look with the benefit of hindsight?

Disclosure: I was one of the four commissioners on the panel in this inquiry.

Background

Site C is the working name of BC Hydro’s latest hydro-electric dam, currently being built on the Peace River in the northeast of BC. Once completed in 2025, it will produce 5,100 GWh of electricity per year (for reference, BC Hydro’s domestic demand in fiscal year F2023 was 54,259 GWh).

BC Hydro has wanted to build Site C for decades. It first applied to the BCUC for permission in 1980, but in 1983 the BCUC rejected the application on the grounds that BC Hydro had not demonstrated either that the electricity was needed, or that Site C was the “only or best feasible source of supply.”

In 2010 the Clean Energy Act was enacted, which exempted BC Hydro from needing the BCUC’s approval to proceed with Site C. After receiving federal and provincial environmental approvals in 2014, the provincial government made a final decision to proceed in December 2014, and construction started in summer 2015.

The project was criticized for its cost and the lack of consent from local landowners and indigenous groups. Some environmentalists objected to the flooding of agricultural land.

The New Democratic Party, the opposition party at the time, criticized the government for its failure to allow an independent review of the project, and promised to hold one if they won the next provincial election, which they did in May 2017.

On August 2, 2017, the government asked the BCUC to review the project, requesting a preliminary report by September 20 and a final report by November 1.

Scope of the Inquiry

The Inquiry was told not to reconsider any previous decisions (such as the ones approving the project), but was asked to advise on the implications of each of three alternatives:

- Completing the Site C Project as planned;

- Suspending the Site C Project while maintaining the option to resume construction until 2024; and

- Terminating the Site C Project and remediating the site.

The government also wanted to know:

- If the Site C project was on time;

- If the Site C project was on budget; and

- Whether there was an alternative portfolio of renewable energy sources that could provide similar benefits at “similar or lower unit energy cost.”

Let’s look back at the Inquiry’s conclusions, with the benefit of seven years’ hindsight.

Paths not taken

The Inquiry concluded that terminating the Site C project would cost $1.8 billion, and that suspending it would cost $3.6 billion. Since neither of these options were taken (the government decided shortly after the Inquiry wrapped up to proceed with the project), there is no evidence today that either of these estimates were wrong, either in absolute or relative terms.

If we were to be keeping score, I’d say no goals so far: nil–nil.

On time (not)

When the government decided to proceed with Site C in 2014, it expected the final generation unit to be in service by November 2024. The Inquiry concluded in 2017 that the project was currently on schedule, but was not persuaded it would remain so. Sure enough, the final generation unit is now expected to be in service a year late: November 2025.

One–nil to the Inquiry.

On budget (also not)

The government asked if the project would be within the budget of $8.335 billion. BC Hydro initially told the Inquiry that the project was on budget and wouldn’t even need the $440 million project reserve held by the provincial government, although it later admitted that it might have to spend as much as $8.945 billion.

The Inquiry disagreed, and concluded that the project was not on budget, and that the eventual cost might exceed $10 billion. BC Hydro currently expects Site C to cost $16 billion.

Two–nil.

“No dam” alternatives

One of the most complex challenges of the Inquiry was to establish whether there was an alternative portfolio of clean energy resources that would have similar benefits to Site C, with an equal or lower unit energy cost. The Inquiry concluded that there was.

Specifically, the BCUC created an illustrative portfolio consisting of wind and geothermal energy which, when combined with demand-side management (energy savings) and industrial load curtailment, would have a unit energy cost of $32 per MWh. This compares favorably to Site C’s unit energy cost of $44 per MWh – assuming the project were to come in on budget.

Armed with this information, the Inquiry concluded that there were “increasingly viable alternative energy sources” that would provide similar benefits to Site C.”

The BCUC’s review of BC Hydro’s current Integrated Resource Plan should have been a useful source of information in this regard. However, as the BCUC noted, BC Hydro “does not identify specific portfolios of resources” to meet its future needs. No help there, then.

The Integrated Resource Plan does say that up to 10,000 GWh of onshore wind is available at less than $60/MWh (Site C will produce 5,100 GWh per year), almost double the Inquiry’s alternative portfolio cost of $32 per MWh. But let’s not forget the cost of Site C is also almost double its budget in 2017, so its unit energy cost will be much higher than $44 per MWh.

I’m going to call this a moral victory for the Inquiry.

Three–nil.

A prickly subject

The load (demand) forecast for electricity informed when the energy from Site C would be needed, and was therefore critical to the analysis. The Inquiry was directed to use BC Hydro’s July 2016 load forecast, which it did. But the government didn’t say the BCUC couldn’t comment on it, which it also did. It’s worth considering the evidence the BCUC had to work with in 2017, and how that looks today.

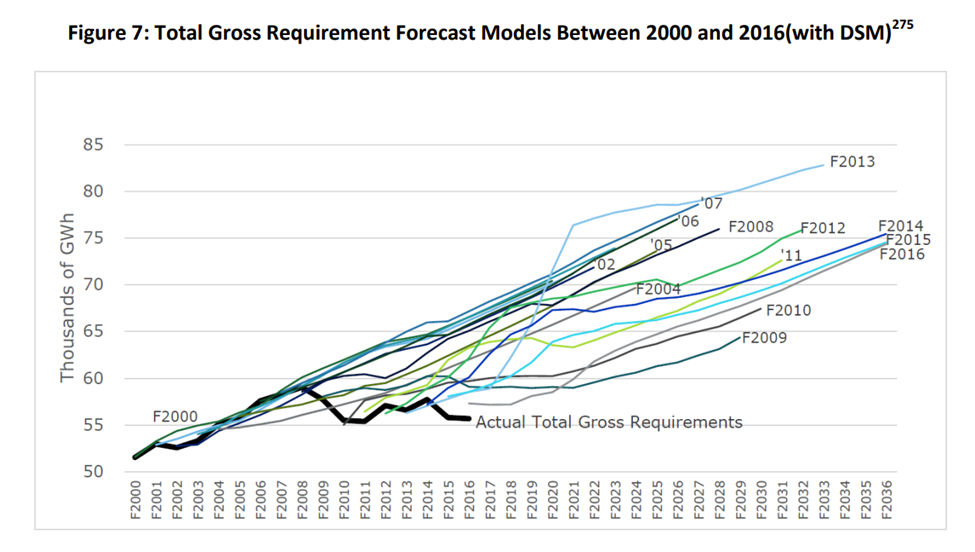

The Inquiry looked at BC Hydro ‘s history of demand forecasts from 2000 to 2016, and presented them in a chart in the Site C Inquiry’s Preliminary Report:

This chart became known as The Porcupine. From fiscal years F2008 to F2016, BC Hydro had consistently been over-optimistic, projecting increases in demand that did not materialize.

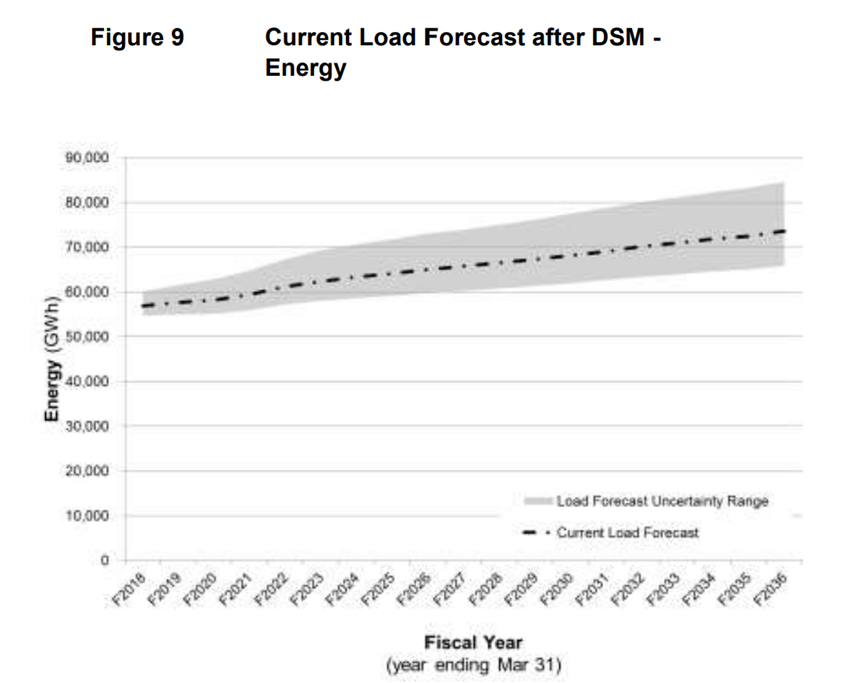

BC Hydro’s July 2016 load forecast, the one the Inquiry was directed to use, looked like this:

Looking at the chart above, we can see that BC Hydro’s forecast demand would be around 63,000 GWh by F2023, with the low end of the uncertainty range being around 58,000 GWh.

BC Hydro added that there was “significant emerging potential” for even more demand from the electrification of transportation and building heat, which was not included in the July 2016 forecast (or even in its December 2020 forecast, produced for the long-term resource plan it submitted to the BCUC in December 2021).

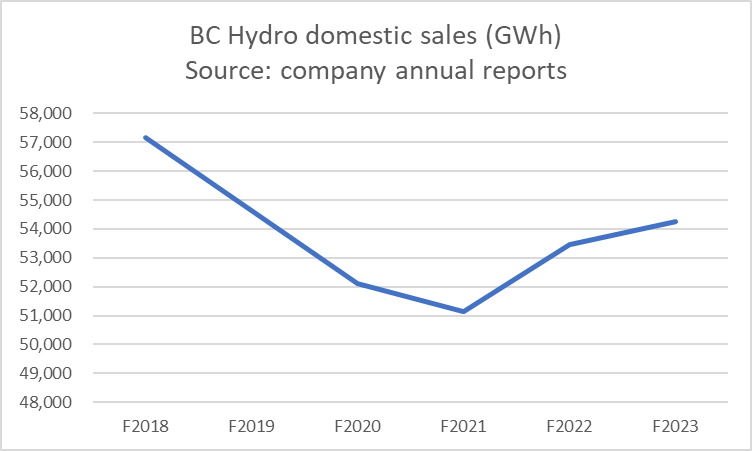

The Inquiry opined that BC Hydro’s load forecast was “excessively optimistic”, and that actual demand might even be less than the low end of the forecast’s uncertainty range. What actually happened after the Inquiry wrapped up? Take a look at the chart below:

Not only did BC Hydro’s demand fail to increase as it had projected, it actually fell, by more than 10 percent. The pandemic alone doesn’t explain this – demand was already falling in F2018 and F2019, and only barely reached the F2019 level again by F2023, the utility’s most recent annual report. The Porcupine has another quill.

The Inquiry has demonstrably been correct so far – by F2023, nearly seven years later, BC Hydro’s demand hasn’t yet reached the low end of its July 2016 forecast of 58,000 GWh. Does that make it four-nil to the Inquiry?

Despite the numbers, there is more circumstantial evidence today than there was in 2017 that BC Hydro’s demand will finally start to take off, as it has repeatedly predicted since 2008. The government appears to be getting more serious about electrification to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in BC’s economy (although it hasn’t made any progress so far), and proposed liquified natural gas (LNG) projects may increase industrial demand for electricity. In anticipation of these trends, BC Hydro is now projecting an electricity deficit as early as 2028, and looking to buy additional energy from private companies.

But there are still reasonable doubts. Industrial demand is fickle, as we saw recently when a global company withdrew its plans to invest in electricity-intensive hydrogen production in Prince George, BC. Demand for electric vehicles in BC has stalled recently. And future governments may not have the political will to force electrification on the public, especially if it entails price increases.

So, I’m going to call this one a draw.

Final score: three–nil to the Inquiry.

Lessons

My scoring of the Inquiry’s conclusions was obviously intended to be tongue in cheek. But there are some important lessons we can take from all this.

The Site C project lacked legitimacy from the start because in the early 2000’s the government bypassed the standard regulatory process – a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity from the BCUC. There was no independent review of whether the electricity from Site C was needed or whether there were better alternatives to providing it. A review by the BCUC would not necessarily have had a different outcome, but it would have allowed public interest groups to make their case, and, if approved, would have given the government a solid defense that Site C was in the public interest.

For a review to have public legitimacy, the BCUC needs to be independent from government. The public must be satisfied that the decision is in the public interest, and not being made by the government to further the interests of BC Hydro, of which it is the sole shareholder. As I’ve written recently, there are questions today about whether the BCUC’s oversight of BC Hydro can be perceived as independent. The government might be wise to provide clear and consistent policy direction to the BCUC rather than taking away its decision-making powers.

A credible long-term resource plan from BC Hydro would serve the public interest. Such a plan should set the stage for future investments in generation, allowing an informed debate on the trade-offs between cost, risk, and the effect on the environment, to name just three considerations. There was no BCUC review of the long-term resource plan between 2008 and 2021; the government took over that responsibility, with no independent oversight. The plan approved by the BCUC in March this year was inadequate, failing to identify alternative portfolios of energy sources that could meet future demand in different circumstances. Again, an independent BCUC that calls out the flaws in BC Hydro’s planning would enhance public confidence.

There are always options. A review in 2010 might have rejected Site C due to lack of demand, as the BCUC did in 1983, but that might have forced BC Hydro to think about smaller-scale alternatives, such as wind power. Ironically this is now what it’s been forced to do owing to the projected electricity deficit. The energy from Site C is likely to be valuable, but it wasn’t the only option in 2010, or even 2017. Or even now.

Conclusion

With the benefit of forty years’ hindsight, the BCUC was right to reject Site C in 1983 – the demand wasn’t there. The forecast BC Hydro created in September 1981 showed annual demand by F1993 would be 59,700 GWh – a level it still hasn’t reached today, thirty years on. Site C would have been a white elephant for decades.

With a mere seven years’ hindsight, the Inquiry’s conclusions are also holding up well. I’m sure there are some that think the BCUC was wrong not to have anticipated the current interest in electrification, but the evidence in 2017 was equivocal at best. The circumstantial evidence today for a large increase in electricity demand is stronger, but let’s not forget that BC Hydro’s demand has still not reached even the low end forecast it submitted seven years ago. There are risks that even the latest demand forecast will add yet another quill to the Porcupine.

All things considered, I think three–nil is a “just and reasonable” result for the Inquiry.