We should understand the real cost of maintaining our energy independence. Are we willing to pay for it?

Introduction

Since 2016, BC’s Clean Energy Act has required BC Hydro to “achieve electricity self sufficiency,” meeting its needs solely from generating facilities within the Province. And yet, it has imported nearly two billion dollars worth of electricity in the last two years.

As demand for electricity accelerates, the gap between the aspirations of the Clean Energy Act and reality is likely to grow, along with the cost of imported energy, much of which is generated from fossil fuels.

The BC Utilities Commission (BCUC) has started to review BC Hydro’s 2025 Integrated Resource Plan, the 20-year view of how it will meet the province’s electricity needs. In its decision accepting the previous plan, the BCUC paid little attention to self sufficiency, merely noting that BC Hydro had demonstrated its compliance with the Clean Energy Act.

It’s time the BCUC took a closer look at the question of self sufficiency.

What is electricity self-sufficiency?

We are self-sufficient in electricity if we can generate all we need from facilities in the province. It would be preferable if the fuel we rely on for that generation was also available in BC, which is true for hydro-electric, solar, wind and natural gas generation.

No-one is ever completely self-sufficient, of course. Our hydro-electric facilities rely on turbines manufactured elsewhere (Brazil, in the case of BC Hydro’s Site C dam, for example). But local generation and fuel source are the key factors.

BC Hydro is, by far, the largest electric utility in BC, serving around 2 million households. The next largest, FortisBC Inc., which serves southeastern BC, only has around 140,000 residential customers. And, like other smaller electric utilities in the province, FortisBC relies heavily on electricity generated by BC Hydro.

So it is critically important that BC Hydro can deliver enough electricity not just to keep the lights on today, but to enable economic growth in the province. And don’t forget that the government’s key strategy for addressing climate change is to use more electricity for building heat and transportation as well.

Energy independence

It’s a choice whether to be self-sufficient in electricity, and how strictly to apply such a principle. In fact, we could choose to import all our electricity from the US and Alberta, saving the cost and effort of building all those dams. So why should we care how much we import? Essentially: security and control.

Energy security is a particular concern at the moment, with the US throwing its weight around in trade negotiations. The less reliant we are on them for energy, the less pressure they will be able to apply in other areas. And Alberta, our other source of imported electricity, is pursuing separation from Canada, however unlikely that might seem.

But energy security will always be an issue. Short-term spikes in demand, for example during a winter cold snap, leave everyone scrambling for energy. Four days into a deep freeze is not the time you want to be relying on the kindness of strangers to heat your home, especially if they have the same weather as you.

Longer-term demand changes can also be problematic. If electricity use continues to increase in the US as it is today to support their growth in artificial intelligence businesses, less is available for us to import. Conversely, if we want to grow our own economy, we want to know the electricity will be there.

Self-sufficiency also provides control over policy decisions such as how “clean” we want our electricity to be. Importing electricity puts us at the mercy of other jurisdictions’ policy choices – for example, how much electricity the US and Alberta choose to generate from natural gas and coal.

Finally, developing our own generation facilities in BC creates construction jobs and can provide economic benefits to specific areas of the province, including First Nations territories.

But then, there’s the cost

There’s a complex relationship between energy security and cost. Imported electricity at today’s prices from the US might be cheaper than adding new generation here in BC, especially if it’s only used occasionally. Having lots of spare generation sitting around most of the time is expensive, even if it can be used to produce some electricity for export.

But it’s important to consider the long term, too. BC expects to need lots more electricity over the next 20 years, both to electrify the current economy and to expand it. If the cost of imports rises as demand for electricity swells across North America, which seems likely, building new facilities in BC could be cheaper in the long run.

In general, though, the more self-sufficient we want to be, the more spare capacity we’re likely to need, and the more it will cost. And this is the crux of the question: How much self-sufficiency are we willing to pay for?

Playing monopoly

Despite what the Clean Energy Act says, BC Hydro isn’t actually required to rely entirely on in-province generation. The lesser-known Energy Self-Sufficiency Regulation gives BC Hydro a get-out-of-jail-free card – it can plan to be self-sufficient only when there are at least “average water conditions”, allowing it to rely on imports when stream flows are below average.

This, then, is BC’s compromise between the aim of self-sufficiency and its cost. BC Hydro must rely on in-province facilities under normal conditions, but can avoid the cost of building extra generation capacity for droughts by importing electricity instead.

Two questions come to mind here:

- Is the self-sufficiency requirement of the Clean Energy Act being undermined by climate change? and

- Is BC Hydro meeting the self-sufficiency standard in its 2025 Plan?

Moving target

BC Hydro plans how much electricity it can generate from its hydro facilities by looking at the average water inflows since it was created in 1962. These statistics are readily available, but may not be giving us the degree of comfort they were intended to.

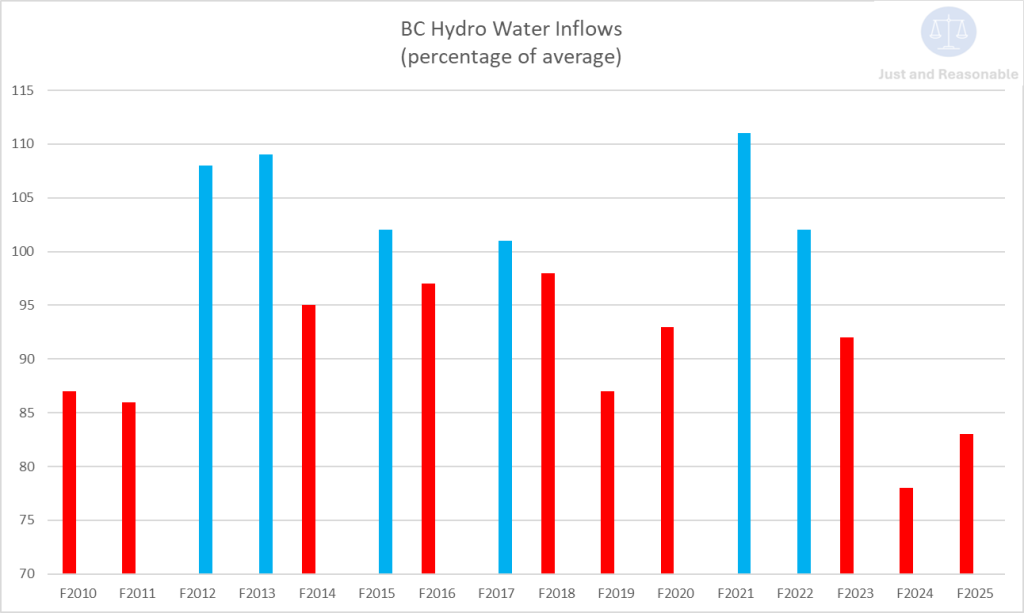

Looking back to F2010, ten of the last sixteen years have been below average:

(below-average inflows are shown in red)

BC Hydro has previously described the 2010 “water year” (F2010/11) as “the lowest in 51 years of record.” It looks like 2024 and 2025 were both worse, which would mean three of the worst years in BC Hydro’s history have been in the last 16 years. In fact, on average these 16 years have been 4.4 percent below the 64-year average.

It’s possible that climate change is permanently affecting BC Hydro’s hydro-electric generation capacity. Rather than using the full 64 years of its history, it might be more prudent for BC Hydro to give more weight to the evidence of the last decade or so. The BCUC should examine this option.

Legal loophole?

Leaving aside imports in exceptional years, the second issue the BCUC should look at is whether BC Hydro’s 2025 Integrated Resource Plan genuinely meets the self-sufficiency requirements even under normal water conditions.

BC Hydro only needs to meet its “mid-level forecasts” of demand from in-province generation facilities, and in 2021 it argued that “mid-level” meant its Reference load forecast. Since this is the one sandwiched between the low demand and high demand forecasts, it sounds reasonable enough. But there’s a problem here.

BC Hydro also stated that the Reference forecast was its “expected or most likely” one. But in both the 2021 and the current 2025 versions of its Plan, the Reference forecast left out significant demand that should be included if we are to do a proper calculation of our electricity self-sufficiency.

For example, the 2025 Reference load forecast doesn’t include enough electricity to meet the government’s climate policies, such as converting buildings to use electric heat, let alone deliver electricity to new mining and LNG businesses that the government says will be served by its proposed North Coast Transmission Line.

To believe this is the “expected or most likely” view of the future, you have to believe that either the government isn’t serious about meeting its own climate goals (possible), and that BC will fail to attract significant new energy-hungry industry in the coming years (also possible).

The result of leaving this demand out of the Reference forecast is that BC Hydro appears to meet the legal test for self-sufficiency, but fails to give us the true picture of the cost to add enough generation to satisfy future needs and maintain the same level of energy independence.

The BCUC should ensure that BC Hydro’s Reference load forecast is truly the “expected or most likely” version, and that BC Hydro has a plan to serve that demand from provincial generation in normal water conditions.

Conclusion

Today’s legislation may be giving us a false sense of comfort about BC’s level of energy independence. Our changing climate and geopolitics suggest we should take a closer look at this question, and the true costs involved.

This is particularly relevant now, as the government pursues electrification to make the economy cleaner. We may be heading for more imports of electricity generated from fossil fuels and more dependence on our neighbours as a result.

The first step is for the BCUC to take the question seriously as it reviews BC Hydro’s 2025 Integrated Resource Plan.